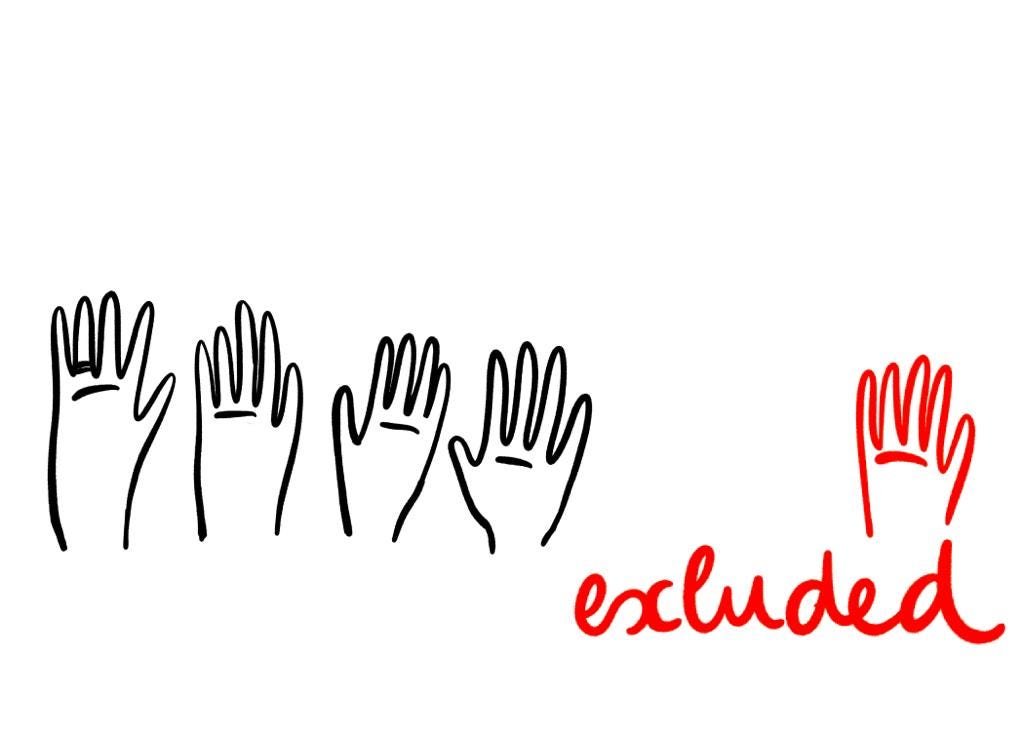

The workers who were left behind

Despite mounting pressure from lobby groups, 3 million UK taxpayers are still shut out from coronavirus support

James Hurley lost his dream job before it even started. In the spring of 2020, he was about to begin work as a campsite assistant in the heathland of Southern England when the coronavirus pandemic took hold. The UK’s national lockdown forced campsites to shut, and his soon-to-be employer terminated his contract. This left Hurley, who suffers from a heart condition, effectively homeless; he’d made early pension withdrawals to buy a motorhome, because a requirement for working on campsites is being able to live on them.

After a long career working in the waste management sector, Hurley, who is 57, was supposed to begin a new season of his life. The previous year, in 2019, he was made redundant from his job at a nuclear power plant and the change in circumstances prompted him to make a big change. He used his redundancy package to take a six-month sabbatical and sail the south coast of England before making a late-career switch as he wound down towards retirement. “Everything was looking absolutely rosy,” Hurley says over the phone from rural Leicestershire.

Then, instead of working on a campsite, he found himself homeless and without an income; hoping to bring in some extra money to see him through, he registered as self-employed, embarking on a freelance career that was never part of his plan. What he didn't know was how little help would be available for someone in his situation –especially in the middle of a pandemic.

Though he struggled to find work, he assumed he would be eligible for government support. But as the UK rolled out a series of relief packages, he was surprised to discover he didn’t qualify for any of them. Gradually, he realised he'd been shut out from the state financial aid – all thanks to the tiniest of details: the start-date on his employment contract. “I was getting ready to start the job, but I hadn't actually started it when we went into lockdown at the end of March 2020,” he says. “And therein lies the issue.”

Because he hadn't started his job yet, he couldn’t be furloughed under the job retention scheme. And even though the UK offers income support for the self-employed, he didn’t qualify for that either, because he needed to have been trading the year prior. After that, Hurley’s only remaining recourse was to claim state benefit payments, but because he had some life savings, he was ineligible.

“I'm one of those unfortunate excluded people, and I still don't understand why,” Hurley says. “Like a lot of people, we’ve just had to help ourselves."

An estimated 3 million UK taxpayers have been excluded from financial support during the pandemic. Their situations vary case by case, but the common thread uniting them is that they tend to work outside of traditional employment structures. Many of them work for themselves or in the gig economy; others alternate between full-time and part-time work; and some of them are people who have taken time off in the past three years to have a child, provide care or grieve.

An investigation by LANCE has found that the gaps in support expose a much bigger problem: Institutional oversight is leaving key parts of the workforce behind, particularly the 5 million workers who were self-employed prior to the pandemic. Combined with eroding workers rights and elected officials ignoring grassroots campaigning efforts, this amounts to a ballooning work crisis that threatens to deepen social inequality and damage public finances.

Over the next three weeks, this series will explore different facets of a question at the heart of the problem: How did the government end up abandoning its freelance workforce? In this week's instalment, LANCE looks at reasons why the UK government's bailout plan leaves out such a large sector of the workforce.

On March 11, 2020, the UK chancellor Rishi Sunak pledged to do “whatever it takes” to support individuals and businesses through the COVID-19 crisis. Delivering his annual budget on the same day that 411 people tested positive for the virus, Sunak announced he was making £12bn in emergency support spending available. In what felt like a hopeful sign for those working outside of traditional employment, he said that £7bn was being earmarked for “the self-employed, businesses and vulnerable people”. He said: “There are millions of people working hard, who are self-employed or in the gig economy. They will need our help too.”

As the pandemic accelerated, the finer details of the package trickled out piecemeal. First, on March 20, the government introduced the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. The furlough scheme, as it’s known, was designed to help employers retain staff by funding up to 80% of their wages (capped at £2,500 a month). There were, however, gaps in coverage that excluded certain employees, including a loophole that locked seasonal and new hires out. Nonetheless, the government said more help was coming and told those who couldn’t access furlough to wait patiently; Hurley, whose eligibility was affected by the loophole, was one of them. “I absolutely believed that I’d be given some support in some way,” Hurley says.

On March 26, three days after the UK went into a national lockdown, the first tranche of support for freelancers was announced. The Self-Employed Income Support Scheme (SEISS) offered a taxable grant worth 80% of average profits for a three-month period, up to a maximum of £7,500. The scheme opened for applicants on May 13, with the first wave of payouts made a few days later. In August, the second round of SEISS, worth 70% of average monthly trading profit, was made available for a further three months, capped at £6,570. In September, the government introduced another extension to cover the six months up to the end of April 2021, paid out in two taxable grants (the second of which is yet to be announced).

Announcing SEISS back in March, Sunak said that “95% of people who are majority self-employed will benefit from this scheme.” He further claimed that it was “one of the most generous in the world” because it targeted support “to those who need help most, offering the self-employed the same level of support as those in work.”

Many workers didn't find that to be the case. Scores of self-employed and freelance workers ticking through the stark application form on the gov.uk website discovered they weren't able to make any claims – often due to frustrating criteria such as their tax status, or when they'd started freelancing. They took to social media, formed grassroots campaign groups and demanded that the schemes be changed – only to find that their cries for help often fell on deaf ears.

One parliamentary petition calling for the self-employed to be included in statutory sick pay during the pandemic garnered nearly 700,000 signatures, but it wasn’t debated in parliament. According to the Petitions Committee website, “Petitions which reach 100,000 signatures are almost always debated.” This one wasn’t, the department for work and pensions explained in its public response, because “It would not be appropriate to require the self-employed to pay themselves statutory sick pay, as they are their own employer. The welfare system provides a safety net to support the self-employed.” Tucked away in a response to a petition, the government was effectively arguing that the self-employed shouldn’t need sick pay because the state would, in theory, care for them should they fall ill. It didn't, however, account for how freelancers were to make up for the lost wages.

By the autumn of 2020, industry bodies and watchdog groups were publishing damning analysis of the scheme. The Resolution Foundation think tank released a report calling SEISS “terribly targeted.” It found that over 400,000 workers were able to claim support despite not losing any income during the crisis, while almost 500,000 people still without work have received no support at all. “The UK’s five million self-employed workers have been at the heart of its jobs crisis,” Hannah Slaughter, an economist at the think tank, said at the time. “Future support should avoid excluding so many groups, while ensuring payments reflect genuine falls in income.”

In November, the Association of Independent Professionals and the Self-Employed published its finding that over 1 million freelancers had been pushed into debt by the pandemic. In a report on the cost of COVID-19 on the self-employed, it found that only a third of sole traders, or unincorporated business owners, had been able to access SEISS, and that number of self-employed claiming the state benefit Universal Credit rose by 341%

Meanwhile, hundreds of MPs have taken up the cause, forming the largest cross-party group of its kind to lobby the government. "Every day that this issue isn’t rectified, I am more shocked by the Government’s lack of foresight,” says Jamie Stone, the Scottish Liberal Democrat MP and chair of the Gaps in Support All-Party Parliamentary Group. “It is blindingly obvious to the rest of us that we will need to rely on the self-employed and small business owners during our economic recovery from this pandemic. Any mistakes that the Treasury makes now will haunt our recovery further down the line.”

There are ten categories of workers who don’t qualify for the government’s £12bn coronavirus support package. The newly employed, people denied furlough, those who earn through tips and anyone made redundant before 19 March were ineligible for the furlough scheme. Meanwhile, the newly self-employed, freelancers with mixed-income, limited company directors, new parents, those in receipt of particular payments (such as a carers allowance, bereavement payments or one-off pension withdrawals) and business owners with over £50,000 in trading profits were all ineligible for SEISS.

Of the groups affected, the largest is freelancers with mixed incomes, which HMRC estimates to be 1.4 million people. These people haven’t been eligible to claim financial support because they fall foul of the so-called 50/50 rule, which requires that “trading profits to be at least equal to non-trading income.” This means that workers can be excluded from SEISS if less than half of their earnings are from self-employment – a situation that can arise, for example, if someone works on a short-term contract basis, or does a mix of freelancing and contract work, or works part-time for an employer while building their freelancing business on the side. When this was questioned via parliamentary petition, the government’s response was that it ensures support “is targeted at those who are most reliant on their self-employment income.”

The situation can be particularly difficult for workers with a certain kind of part-time or contract job. Despite working for themselves, many freelancers pay their tax at source, as employees do, but without the associated employment rights. Zero-hours workers – also known as PAYE freelancers, because they pay tax through the Pay As You Earn system which deducts it directly from their paycheque – can’t be furloughed, because they’re not employees. But they also can’t access SEISS if they make more than 50% of their income like this. Often, workers have no say in this matter; in certain industries, including film and TV, it’s become the norm to work in this way.

One production manager who’s worked in the TV industry for over 20 years, and who wishes to remain anonymous, says she never wanted to be taxed at source, but that “more and more in the TV industry, this is not possible.” With production mostly on hold during the pandemic, she says, “I now am not entitled to anything despite paying taxes for over 20 years. I have used up every penny of my savings, and I am reliant on my husband to try to cover everything.”

Journalist and presenter Ellie Phillips, a spokesperson for Forgotten PAYE – the largest group of independent workers who didn't make the cut – says that PAYE freelancers are in the worst situation of all. “They're taxed at source, on the highest rates of tax, but yet they don't have any of the benefits of being a self-employed individual. No work guarantee, no sick pay, no maternity pay, no redundancy pay and now no support.”

Phillips, herself a PAYE freelancer ineligible for support, explains that the furlough and SEISS packages only target self-employed people and employees, while missing out on a third category, which she describes as “independent workers.” These are PAYE freelancers, zero-hours workers, or those who have mixed-income streams, “all of which the 50% rule discriminates against,” she says. Many freelancers in the creative sector fall into this category, where it’s common to pick up short-term PAYE contracts which amount to more than 50% of their total income.

Furlough for these workers is at the discretion of companies, which have no legal obligation to assist their freelancers. Some employers, including the BBC, chose to extend furlough to their PAYE freelancers last year, but many other companies have not done the same. The industry body Women In Film and Television found that just 16% of PAYE contractors have been furloughed by their employers, while research from the media and entertainment union Bectu estimates that only 2% have been furloughed. It’s not only the creative sectors affected by the 50/50 rule. According to Forgotten PAYE, mixed-income and zero-hours are widespread across the UK. Additionally, the income that pushes someone over the 50% mark, disqualifying them from SEISS, doesn’t have to come from just earnings; payments from investments or a pension also count.

In January of this year, the Institute of Fiscal Studies published a briefing which found “clear injustices” with the way people were excluded from SEISS. The IFS’s research found that while providing support for some of the excluded groups poses technical challenges, that’s not the case for all groups, including PAYE freelancers. “The government has actively chosen to exclude these people from SEISS,” it said.

Nearly a year into the pandemic – despite mounting pressure from all sides of the political spectrum, grassroots campaigns and watchdog analysis – little has changed. While the furlough scheme and SEISS have been extended and small tweaks made, the core eligibility criteria remain largely the same. And James Hurley, one of the 3 million taxpayers that have been left behind, is still waiting for answers.

By the time the third round of SEISS was announced in November, he was still unable to claim; but because he’d drained his life savings, he’d become eligible for Universal Credit, at just over £400 a month. Currently, he’s applying for freelance contracts in waste management, his former professional field. Because he doesn't qualify for housing assistance, he’s been living on a gutted narrowboat with no heating.

He doesn't know if he'll ever be eligible for government grants, but is focusing on what he does have: his family’s health. “My mother’s 84, and she just had her first jab two weeks ago,” he says through tears. In spite of everything he's been through, Hurley is pragmatic. He doesn’t want pity; he just wants to know how a responsible citizen could be forgotten in this way. “Mr Sunak said nobody would be left behind and I believed him,” he says. “I've always paid my taxes, no different to anybody else. I did my job: stay home, protect the NHS, save lives. And then I was told that I don't fit the criteria.”

The education sector is another that has been hit by several of these exclusions / supply teachers whose agencies have refused furlough and those employed directly by schools on 0 hours contracts - the latter can not be furloughed.

Examiners are often taxed at source via PAYE but on self employed contracts. They are not employees but can’t be furloughed, yet mostly fall foul of the 50:50 rule due to being taxed at source. The cancellation of exams in 2021 has destroyed any remaining hope of an income for this year.

Companies, speakers and providers working with schools (visiting music teachers, self employed workshop leaders, animal charities, dance teachers, extracurricular sports providers, etc.) have all been excluded too.

I am self employed, part of a partnership. I am excluded because trading profit needs to be higher than non trading. In 2017 I’ve invested 70k in my business. 2017-2018 ( 5 months of trading) I had a loss because of big investment, 2018-2919 was very good and balanced out the previous year. 2019/2020 wasn’t included. This rules me out. I had no income since march2020 and I am not entitled to anything. I am paying taxes for 16 years, I also had to pay 19/20 tax even if I didn’t receive any help. I am very close to lose everything. It is absolutely disgusting, huge discrimination! Maybe Rishi Sunak could give me advise how should I live, feed my children and pay bills?!