One of my most-read newsletters is a post titled “Am I still a journalist?”

It’s an essay I wrote two years ago when I was caught in a thick fog of a career crisis. My first book had just come out, but I wasn’t feeling particularly successful. I was disillusioned by the media industry. My pitches weren't landing, mass layoffs were happening and I was questioning all of my career choices, including whether I could even call myself a journalist anymore.

Here, I revisit that question. I’ve re-published the original essay and annotated it with my thoughts on what’s changed, and how I’ve been feeling, since then.

Am I still a journalist?

In April 2021, the author and former New York Times reporter, Jamal Jordan, tweeted about how journalism schools need to teach a module on lay-offs.

In what turned out to be ominous foreshadowing, HuffPost UK’s editor-in-chief announced that the news desk was closing and journalists were being made redundant.

So I was actually wrong on the timeline here – Jordan posted that before the HuffPost UK news. But that’s neither here nor there, because in the two years since that tweet (x?) the media industry has circled ever closer to the drain.

If things felt bad in 2021, it’s only worsened since. Job cuts in the media, specifically in news divisions, rose by more than 20% in 2022. This year alone, Buzzfeed News shuttered, Vice News Tonight went off the air and its parent company, Vice Media, filed for bankruptcy. And the Washington Post, NPR and CNN are just a fraction of the outlets that announced significant layoffs. Oh, and let’s not forget about Elon Musk blowing up Twitter.

The big narrative here is that journalism's ill health isn't just a death knell for the industry, but for democracy itself. Without a robust media, how does the public hold politicians, corporations and general baddies, to account? While painfully accurate, that analysis misses the point of what it feels like to work in an unhealthy business. We often talk about journalism as a "struggling sector," but at its coalface are individual workers who can’t make a living. Even though we work in a field that’s supposedly essential to democracy, we continue to face job insecurity, low pay, and demoralizing working conditions.

The impact of the dsyfunction reverberates beyond money trouble. My personal struggle isn’t a financial one – I transferred my skills into other sectors and make more money than I did from my media jobs. My worries are existential in flavour. I feel deflated, uncomfortable and worn down. Put simply: I just don’t feel good about my career.

So yeah, journalism schools still need that layoff module. As someone who went freelance after losing a job in the media, I know how painful it is to go through redundancy, but even worse, how probable it is, too. Ever since it happened to me, I tell every journalist I know that it’s not a matter of if but when you lose your job in the media industry. What does it say about the media industry that I feel more secure in self-employment than I did in a staff job?

A few months after I published that OG newsletter, I wrote a magazine piece about how our work past impacts the trajectory of our careers. A therapist I interviewed for it told me that maybe my double-downing on self-employment was a reaction to toxic work environments. She said: “Really challenge yourself to ask ‘Am I hiding here? Or am I doing this because this really is a better choice for me?’ We can really convince ourselves of the answer to that. Even when it might not be quite true.”

What I took from our conversation was that we can overcorrect in our careers just like we do our romantic lives – whiplash from the bad boy to the nice guy. I knew that my fear of job loss had cast a long shadow over my career, but I didn’t realise the extent to which I’d turned past negative experiences into absolutes. I’ve developed this warped fear of taking a toxic job only to lose it. I wonder how many opportunities I’m not even willing to entertain because of it.

No interview has ever haunted me as much as that one does.As much as going freelance has been a boon for my career, the time I spend on what I call “traditional journalism” (reporting and writing features for mags and rags) has been an exercise in screaming into the void. My pitches go unanswered. Not because I don’t know how to pitch or who to send them to, but because the pitching system is broken. On top of paltry rates, I pay the emotional tax of chasing late invoices.

All this has left me thinking, can I – or indeed do I even want to be – a journalist working under these conditions?

Short answer: No.

My pitching-to-commissioned success rate has been 100% this year. Editors have greenlit all the stories I pitched them – all four of them. Writing so few pieces for “traditional media outlets” used to bother me; lol when I worked at Vice we churned out four pieces in a MORNING. But then this year, I had a realisation: I pay for the New York Times to play the Spelling Bee.

Until recently, I had a misguided belief that as a journalist, I needed to be able to support myself entirely from my journalism. I mean, it makes sense – my friends who work in accountacy, law, media, advertising, government, finance and advertising all do so. But those are not the creative sector. The NYT is an outlier, succeeding in part because of its non-news revenue streams: recommendation sites, cooking and puzzle apps. To quote myself (lol): “The news industry, as a whole, cannot support itself financially with its own journalism. So why was I expecting to be able to do it in my media business of one?”I want to be able to say I stay in journalism because I believe in the power of the fourth estate. And that I know that the business model will eventually work itself out because democracy will always need journalism. It’s earnest and it’s all true, but I also can’t in good faith pretend that’s the only reason. If I’m really honest with myself, I rattle around in this broken industry because I like being able to call myself a journalist. It’s a huge part of my identity – it’s what makes me, me.

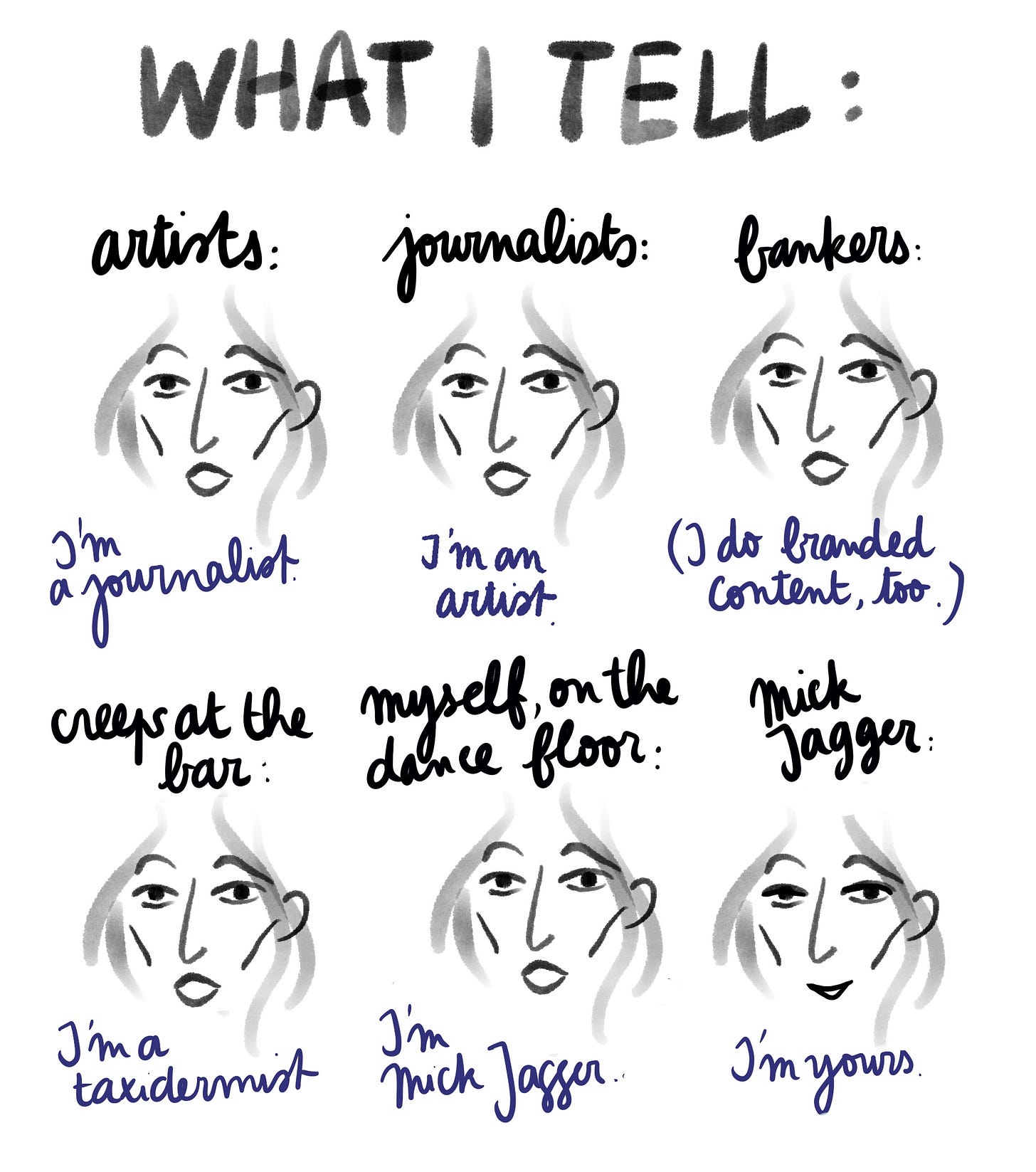

In a land and time far, far away, I used to go to parties and tell people that I was a music journalist. My bum clenches with embarrassment at how cool I used to think I was. But back then I didn’t know where my work ended and I began. To a large extent, that’s still the case, but the difference now is that I’m aware of how complicated – and toxic – my relationship is with my work. I’m codependent on my job title.

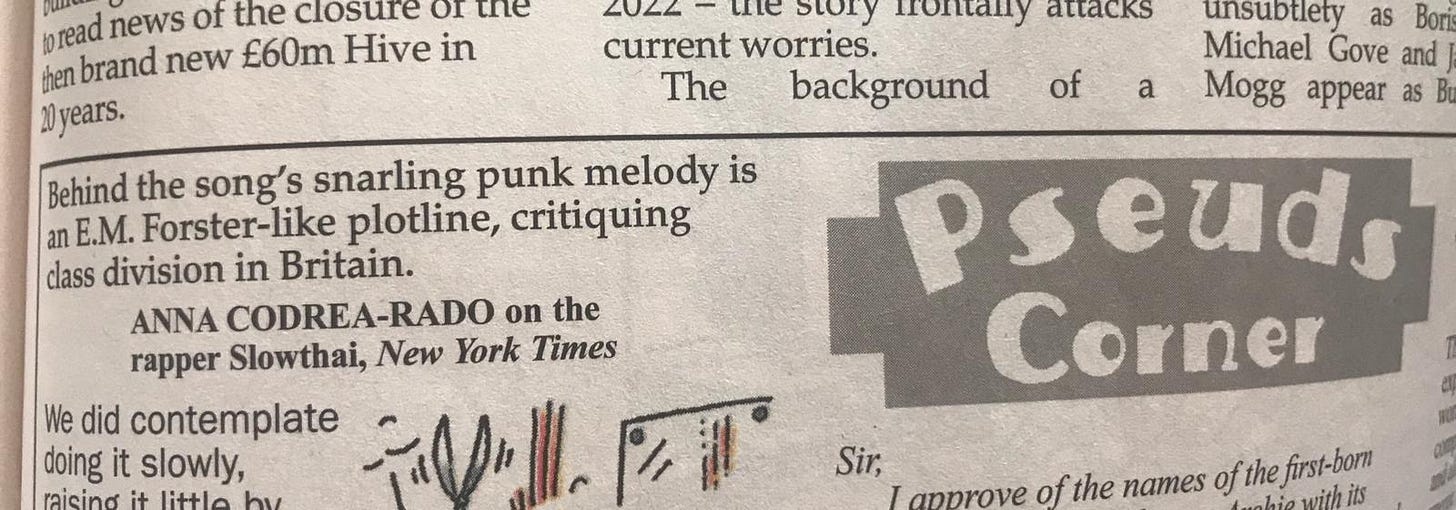

This year marked my sixth freelancing anniversary. In that time, I’ve done some really cool work. I wrote a book for a Penguin imprint. I had a front page byline in the New York Times. I was shortlisted for a British Journalism Award. I wrote for the Paris Review. And my personal favourite: I got dragged in Psueds Corner.

Note how I qualified all those achievements in relation to an institution, and legacy ones at that. I’d love to say that I only need internal validation for my work, but that’s just not true. I don't want to care where my work appears, but the truth is that I do.

In a twist of irony, I used to want to write for the NYT because I was desperate to reach my perceived pinnacle of bylines – now I want to write there just want to prove that I still can. To whom? I'm not entirely sure.Someone asked me recently if the solution is just to stop referring to myself as a journalist and say that I’m a writer instead. Maybe it is that simple. But if that’s the answer, then why can’t I just do it?

I’m still frustrated with the industry, but my edges are also sharper. I don’t berate myself quite so harshly for struggling to make it work. My sense of self-worth is still enmeshed in what I do, but I’m working hard to untangle it. There’s a long way to go but I think I’m making progress. I just call myself a writer now. Thanks for reading A-Mail. If you enjoyed this newsletter, press the little heart button, forward it to a friend and if you really like what you read here, consider financially supporting it

You beautifully describe what it is to be a creative. We seem to define much of who we are from our creative efforts. Your piece reminds me of the day when I realized that Facebook, Google and Amazon don't need journalists to get the attention of readers like newspapers and magazines did. That journalism wasn't primarily about what was covered. Journalism only existed to get eyeballs on the ads. And about the same time I realized that my whole creative career in brand design and corporate communication design was about promoting corporations that created global warming among other bad for us stuff. I'm hoping that a better future for creatives is emerging in alternative media and direct to consumer opportunities. Thank you so much for your thoughtful post.

Thanks for writing this. Did kinda hit home. I'm constantly fluctuating between calling myself a 'journalist' and calling myself a 'writer', depending on the context (and my level of insecurity / imposter syndrome at that particular moment). But I think I'm becoming more comfortable with the latter now...